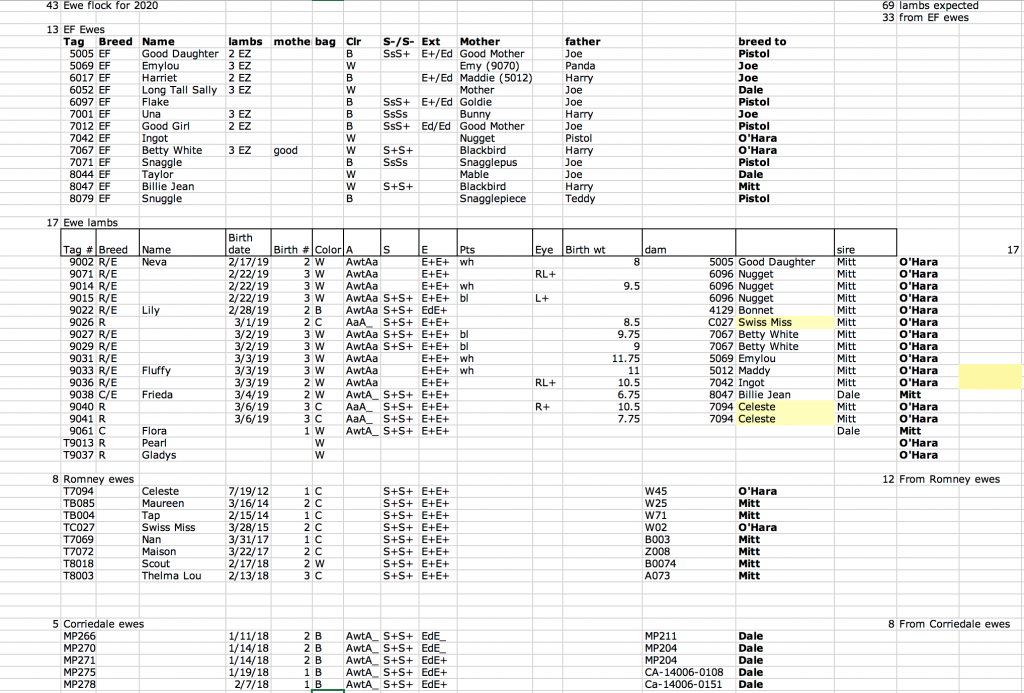

It is breeding season, and that involves a lot of careful planning. First, there is the question of who to breed to whom. I make a spreadsheet with all of our ewes, which includes all of the important data about them. The first challenge is to avoid too much inbreeding, but there are other considerations. Now that we are breeding for colored fleeces, I need to consider the color genes carried by each ewe, which includes whether she has the dominant black gene (Ed) common in our East Friesians and Corriedales, the spotting gene (Ss) that is present in many of our East Friesians, the dominant white gene (Awt) or the recessive color alleles of that gene (A_) we brought in with our Romneys. East Friesians who are white don’t have the dominant black (Ed) gene, and if they have brown noses and feet that means they don’t have the spotting mutation (Ss) and so they are the best candidates to breed to Mitt or O’Hara, the Romney rams we are using this season, because their offspring will carry recessive color genes without the spotting that can pollute their gorgeous fleeces. We had tan ear tips on some of our white Corriedales, which, according to our genetics guru Margaret Howard, carries the tantalizing possibility that they harbor a recessive color gene that is being masked by their more dominant white gene. So we are breeding Flora, our one white Corriedale ewe lamb, to Mitt. He carries two recessive color alleles, so if Flora does have a recessive color gene, there is a 50% chance she will have a colored lamb. And Mitt’s color alleles are THE most recessive on the spectrum, so Flora’s colored offspring would tell us what color gene she carries. I could go on and on, but you get the picture–it is complicated. The spreadsheet below helps me make all the individual decisions. I also try to estimate how many lambs to expect; with the East Friesians we know twins and triplets are the norm, so we plan on 250% lambing overall (2.5 lambs/ewe). The ewe lambs and fiber sheep have lower rates, but with only one year of experience, we are still guessing a bit about lamb expectations with them.

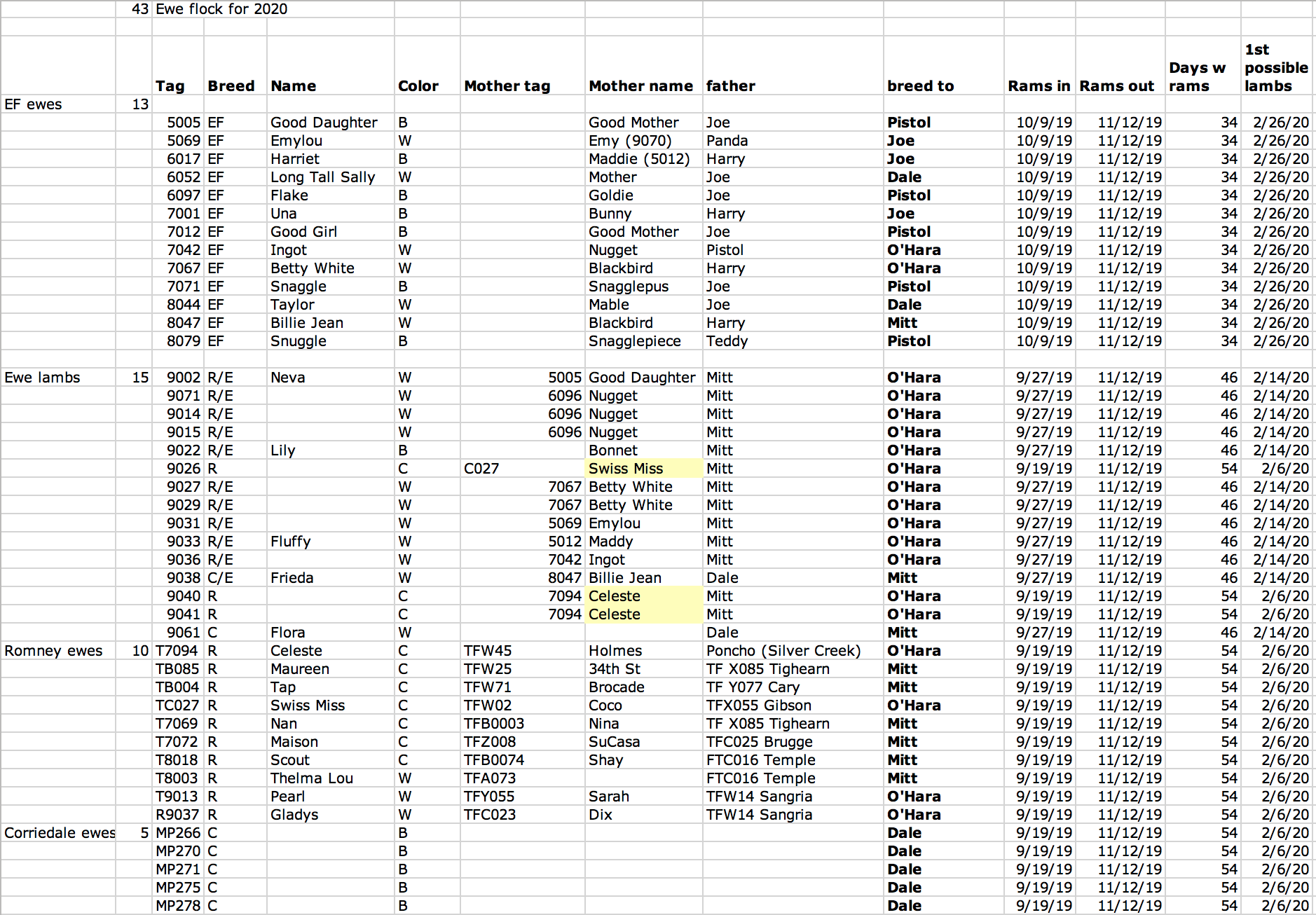

We also have to consider when we want lambing to begin, and that involves another spreadsheet. Once I’ve made the decision about all the “arranged marriages,” as my husband Corey likes to call them, I make a spreadsheet that helps calculate when to schedule the “wedding days.” Our experience with the East Friesians is that the first lambs will be born 139 to 140 days after the rams go in, and lambing will be in full swing at 142 to 144 days. We like to begin lambing right around March 1st, which means putting the rams in around October 9. The East Friesians don’t waste any time getting down to it…sometimes we have ewes being bred in the corrals before we even get them back to the pasture, and generally all the ewes are pregnant after one heat cycle (17 days), so we take the rams out after about 3 weeks. Last year we learned the hard way that libido is not that high in all breeds, and our Romneys and Corriedales did not all get pregnant. So this season we are staggering the breeding, to give everyone the time they need. Our Romney and Corriedale girls went in with their rams on September 19, and we added the hybrid girls–our “Romnesians,” who are half Romney half East Friesian (so we figure they will be somewhere in the middle statistically) and Frieda our one “Friedale,” who is half East Friesian half Corriedale–yesterday on September 27. The East Friesian ewes will go in on October 9. There is still a lot of uncertainty, because one of those Romney ewes COULD get pregnant on her first day. We haven’t worked out the average gestation period for the Romneys yet, but we have to consider that we could have lambs as early as about 140 days after September 19. A calculation on the spreadsheet pops out that number: we need to be ready for lambing by February 6. Yikes! It could be a long drawn-out lambing this year. But the Romneys and Corriedales are easy lambers, one of the reasons we are making the transition, so we won’t be in full-round-the-clock lambing mode until late February. (I hope.)

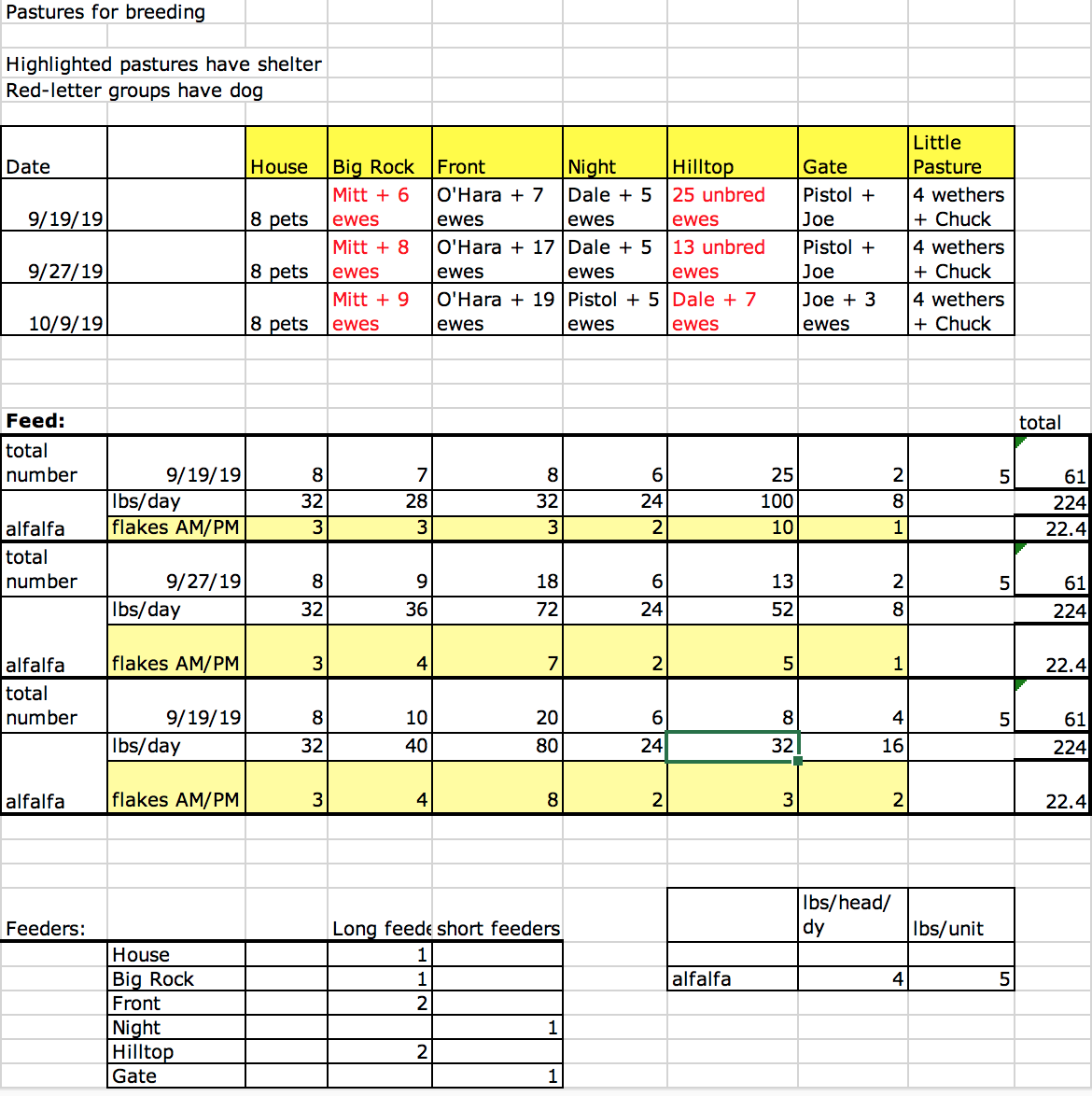

There are other decisions to be made also–we are using 5 rams this season: Pistol and Joe, our two East Friesian rams, will each get a small number of ewes, so that we have some pure East Friesian lambs to sell as dairy breeding stock. Then we have Dale the Corriedale, who will breed our 5 Corriedale ewes and a couple of East Friesians, and two Romney rams, Mitt the Romney, and O’Hara who is borrowed from Tawanda Farms, who will breed all of our Romney ewe lambs, the “Romnesians,” Flora the Corriedale (who can’t be bred to Dale because he is her father) and Frieda the “Friedale.” That means we need 5 pastures with breeding rams in them, and we try not to use pastures that share fences, because the rams may get to fighting across the fence. We need a place to keep wethers (and Chuck, our adorable Romney ram lamb from Tawanda Farms, officially named Charleton Heston, because his mother was named for a character in Ben Hur) as well, and everyone needs a shelter because it might rain. That is another puzzle to solve, made a little easier by the fact that we now have two portable shelters that can be moved to the pastures with no shelter. Oh yes, there is also the matter of our two protection dogs and where to put them so they do the best job of protecting 7 different pastures with sheep in them. Another spreadsheet comes in handy.

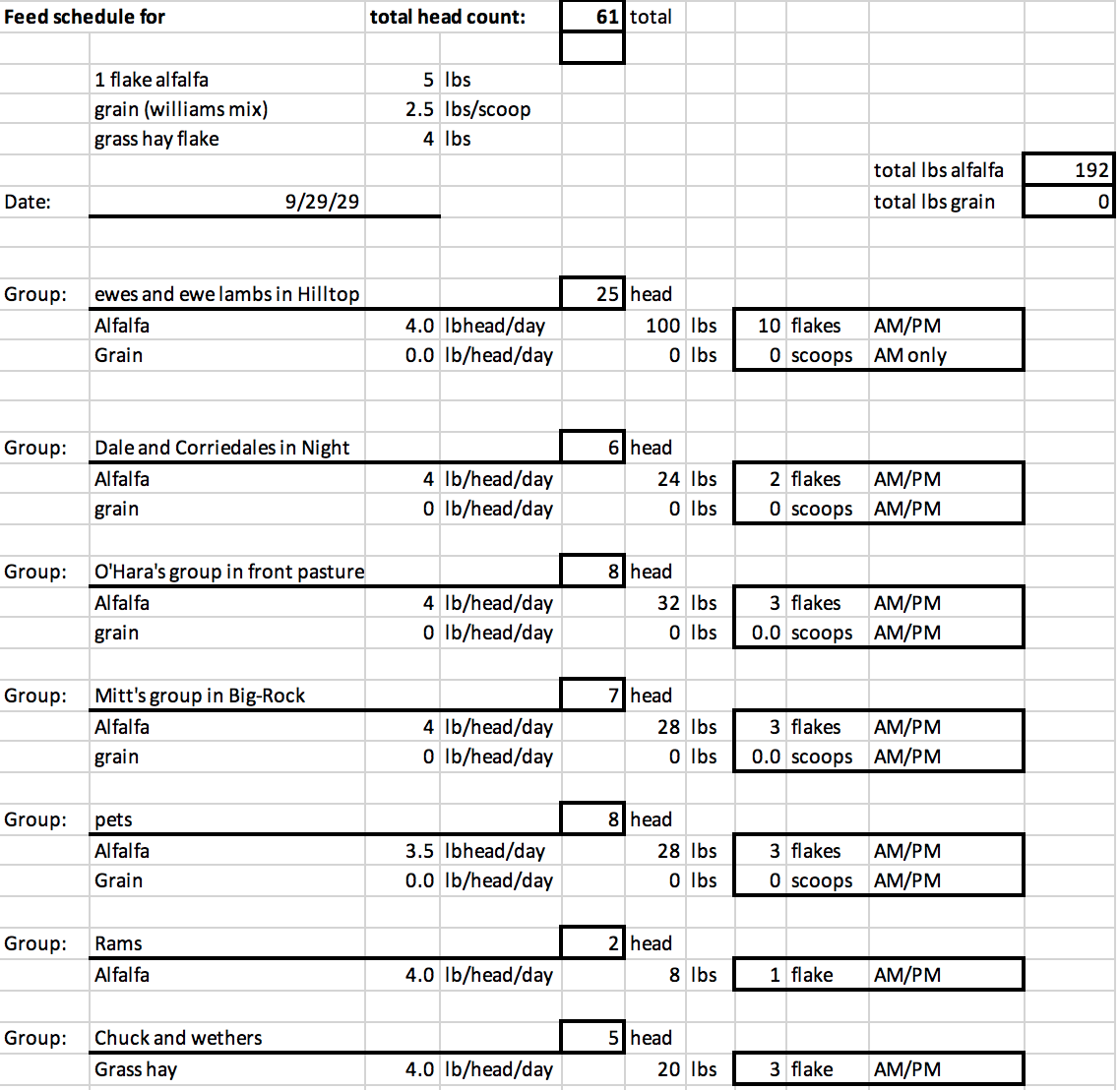

And finally…how much do we feed everyone? One last spread sheet and we are almost done.

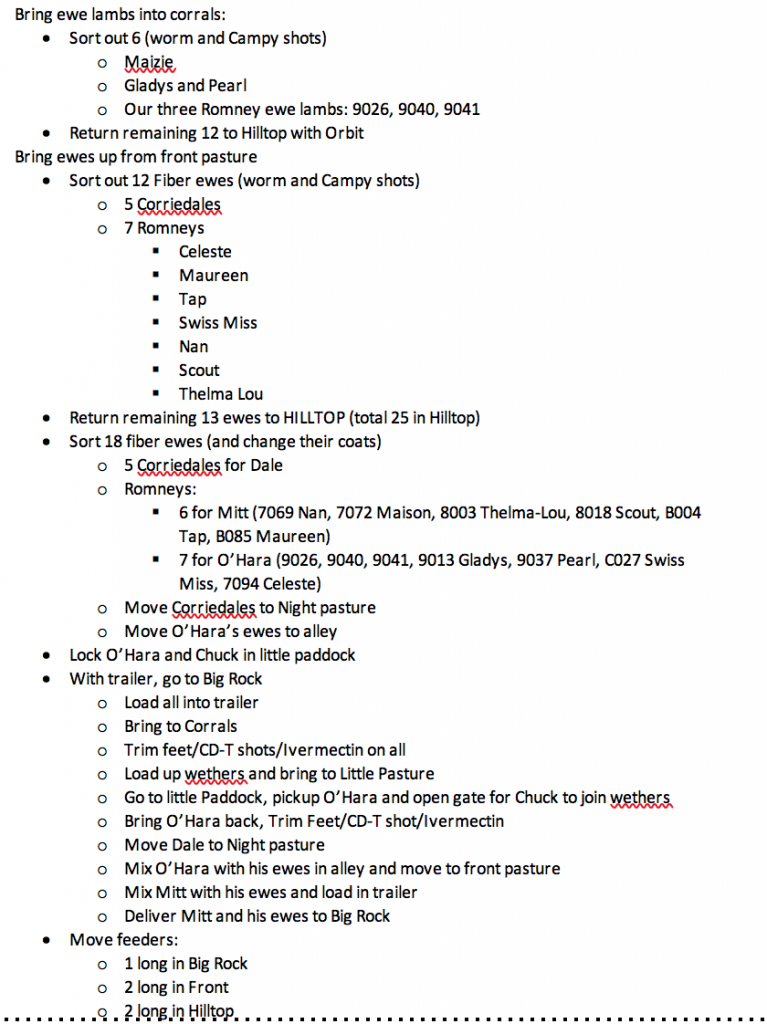

All that remains is how to get everyone to where they need to be on breeding day. Decades ago, when I was an undergraduate at Bowdoin, my oceanography professor said something I never forgot: “You can’t think at sea.” His point was that you needed to create detailed protocols (step-by-step procedures) to take you through the experimental work you would be doing on your ocean voyage. That lesson came in very handy in my 6 years of graduate research work at the Salk Institute. “Protocols” are key to every successful scientific experiment–spell out in advance exactly what you are going to do, and then follow the protocol. The same is true on a sheep ranch. I find that it really helps to write out a detailed protocol with a step-by-step plan. In the morning before we start moving sheep, Lolo, Lisa, Melinda and I go over the protocol together to see if there are any flaws in the plan. We make sure that we have the right sequence and aren’t trying to move sheep through a pasture that already has sheep in it, or any other glitches like that.

Finally!! DONE! Now it is all up to the rams and the ewes, and in December we will have our vet, Dr Dotti, out to ultrasound all the girls and tell us when to expect lambs!